Joseph Bonsall

FATHER OF RICHARD BONSALL “THE IMMIGRANT” a genealogic brick wall finally dismantled

by: Ray-Scott Miller

Roystone Rocks near Mouldridge Grange in Derbyshire. photo credit: James Pedlar www.jamespictures.co.uk/

Acknowledgements

This work is dedicated to Robert A. Bonsall. “Bob” Bonsall passed in 2021 before realizing his lifelong dream of discovering Joseph Bonsall’s father. He was a fervent genealogist, always available to troubleshoot a challenging generational step. Without Bob’s ethical work on the ancestry of the Bonsall family, this paper would not be possible. My hope is that this research carries the torch for Bob and finishes the work he started well before my own birth. One of Bob’s favorite quotes exemplifies his giving nature and perhaps how we all should approach genealogy as a vocation.

“They threw the torch of service to us. Be it ours to pass it on.”

Thank you to the original members of the Peak Gene Group, John Pegg, Tom Miller, Max Kennedy, and John Milward. They exposed me to the uniqueness of E-PF2431 in Britain. John Pegg mentored me in the historical research of the members of the E-PF2431 haplogroup and the group’s associated regional history, Tom Miller provided the snide remarks necessary to stick with such a long project, Max Kennedy ensured I crossed my “t’s and washed my dishes, and John Milward provided the Milward patriarchal persona, which one desires to impress.

Than you to Yacine Kemouch, who worked tirelessly on the phylogeny of the E-PF2431 haplogroup.

Furthermore, I am grateful for the genetic contribution of David Milward, who passed in 2021, which continues to impact the research of the Peak Gene Group, albeit now through his loving wife.

For the Amazigh people of North Africa

Médéa, Algeria, likely North African Roman origin of PF2431 in Great Britain. photo credit: Ath Salem www.instagram.com/athsalem/

Introduction

For decades, Richard Bonsall “The Immigrant” of Mouldrige Grange, Derbyshire, and Darby, Pennsylvania, has attracted accomplished genealogists and inspired a significant body of historical research. However, a genealogical brick wall has stood impenetrable beyond Richard’s father, Joseph Bonsall. Now, with commercial genetic testing, DNA, in coordination with traditional genealogical research, provides the extra push needed to topple such a long-standing brick wall.

Richard Bonsall “The Immigrant” belongs to the haplogroup E-PF2431, but more specifically, a node with the E-PF2431 phylogeny defined by the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), FGC19003. The association of E-PF2431 with Richard Bonsall is proven by the DNA test results of two living Richard Bonsall descendants from two different sons of Richard Bonsall. More broadly, within the E-PF2431 phylogeny, two other closely related genetic lines appear within the range of traditional genealogic research, yet with different surnames: Miller and Milward. The association between these two gentic line and the Bonsall line evidenced a surname change between Milward and Bonsall at some point in the past, with no indication of the direction.

However, traditional genealogic research into the Miller family line proved the original surname for the Miller was Millard and very likely Milward before Millard, thereby placing the Milward surname both upstream and downstream from the two Bonsall samples. Thus, the Bonsall phylogenetic position between multiple Milwards provided a direction for the surname change, which is from Milward to Bonsall, estimated to circa 1600. Therefore, the research began to find the connection between the Bonsall and Milward families, produced by some non-paternal event (NPE).

Almost all genealogic sources list Johanna Milward Stone as Joseph’s mother. However, confusion around whether Johanna’s maiden name was Stone or Milward stopped the genealogical efforts from progressing. Nevertheless, Richard Bonsall, husband of Johanna in 1620, was not the father of Joseph Bonsall, as many believed. In fact, there is no record of Johanna and Richard Bonsall bearing any children, whatsoever.

Johanna was married prior to Richard. Her first husband’s name was William Milward, whom she married in 1590, Alstonefield, Staffordshire and with whom she bore many children. Once Johanna remarried with Richard Bonsall, her minor children in 1620, including Joseph Bonsall, assumed their stepfather’s surname. All subsequent generations descending from Joseph Bonsall maintained the Bonsall surname. Thus, an accurate Bonsall pedigree can be illustrated headed by William Milward and Johanna Stone. (figure 2)

Bonsall Pedigree

Figure 2

St. Giles Church, Hartington, Derbyshire. photo credit: Steve Bark (Tumblr)

Section 1: Identification of Richard Bonsall’s Haplogroup

Richard Bonsall, “The Immigrant,” was baptized in St. Giles Church in Hartington, Derbyshire, on March 17th, 1641. Richard then emigrated to America from Mouldridge Grange, near Pikehall, Derbyshire, in 1682.[1] When he arrived in Darby, Pennsylvania, Richard became a prominent Quaker citizen, well-established as a leader within his community. Though some of Richard’s children were born in England before his emigration, two sons named Benjamin and Enoch were born after Richard arrived in the Quaker enclave of Darby Township.[2]

Bonafide direct paternal descendants from Enoch and Benjamin tested their Y-chromosome through FamilyTreeDNA.com (FTDNA). The two descendants (R-Bonsall and G-Bonsall listed in Table 1) have a genetic distance of seven when comparing their 111 STR marker tests.[3] For members of the E-PF2431, the 111 STR test is sufficient to show a close relationship, if the samples are located in Northern Europe or Great Britain.[4] Moreover, G-Bonsall and R-Bonsall have well documented genealogies showing descendancy from Richard Bonsall “The Immigrant.” Thus, there is no doubt Richard Bonsall “The Immigrant is the common ancestor of the two Bonsall samples.[5]

Furthermore, the genetics and the traditional genealogy prove that no NPE has occurred within the male Bonsall lineage from Richard “The Immigrant’s” birth (prior to 1642) to the birth of R-Bonsall and G-Bonsall. Both descendants of Richard Bonsall carry the Bonsall surname and were assigned the yDNA haplogroup, E-PF2431, from their respective genetic tests. Thus, one can assign Richard Bonsall to the same haplogroup.

Appendix 1 lists all closely related genetic matches to the Bonsall Samples, who have tested their Y-chromosome with FTDNA.com. All the samples listed are of the haplogroup E-PF2431.

E-PF2431 represents a SNP most common amongst the Amazigh culture of North Africa and rarely identified in Great Britain or Northern Europe.[6] Because of E-PF2431’s extremely low saturation in Great Britain, tracking familiar relationships are far less challenging than many other haplogroups within the same geographic region. A mere 12-marker STR test is sufficient for the identification of E-PF2431 haplogroup members in Great Britain. However, refining members to a specific node within the E-PF2431 phylogeny requires deeper SNP testing, such as the BigY-700 test from FTDNA.com.

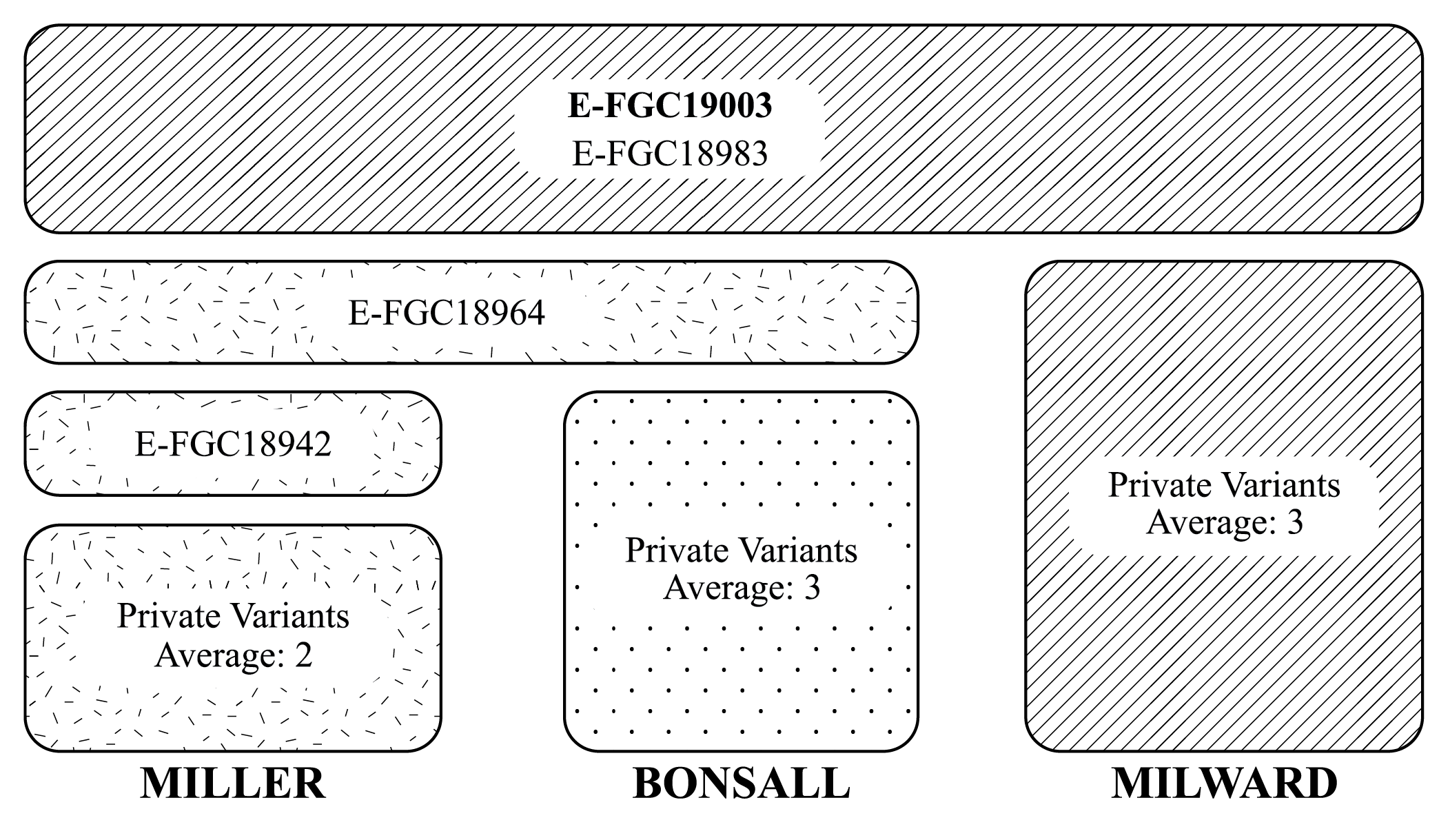

G-Bonsall was administered the BigY-700 test from FTDNA, which claims 90% coverage of the Y-chromosome’s genealogical significant regions.[7] From G-Bonsall’s test results and similar tests performed on closely related individuals with common ancestors within the range of traditional genealogical research, a phylogenetic node defined by the SNP, E-FGC19003, was identified, grouping five individuals with three distinct surnames (Bonsall, Miller, and Milward) within the node. Setting aside the apparent etymological connection between Miller and Milward, the SNP Bock Tree (figure 3) from FTDNA, provides a visualization of the relationship between the three surnames.

Block Tree of E-FGC19003

Results from FTDNA E-PF2431 Project

Figure 3

The SNP defining the Miller/Bonsall node is FGC-18964. FGC19003 represents the common ancestor between all five samples: R-Miller, T-Miller, G-Bonsall, J-Milward, and D-Milward[8]. FGC18964 (Miller/Bonsall) is a more recent mutation than FGC19003, hinting that Milward is the more ancient surname for the Bonsall paternal ancestry. Furthermore, Yacine Kemouche constructed an E-PF2431 phylogeny which shows that the Bonsall/Miller coalescence, is approximately 1620±170 CE. Kemouche dates the D-Milward and J-Milward coalescence to approximately 1605±195 CE, providing further evidence of the Milward surname antiquity. However, this paper will refine the Miller/Bonsall date of coalescence and its margin of error through more traditional means to about 1609±3 CE.[9]

Though Kemouche’s margin of error allows for a more recent coalescence between the two Milwards versus the Milller and Bonsall samples, the Milward coalescence is more likely the earlier given Kemouche’s estimates and other evidence contained within this research.

North Fork of the Shenandoah River from Main Street bridge in Timberville, Virginia. photo credit: Kipp Teague www.retroweb.com

Section 2: Miller, Millard, Milward

The traditional genealogical work on R-Miller’s oldest known ancestor, John Miller “The Quaker” of Augusta County, Virginia, provides further evidence of Milward as the original surname for the Bonsalls. John Miller of Augusta County, Virginia, was born circa 1700, died in 1781 in Lincoln County, Kentucky, and appeared in numerous historical records, including a Kentucky Supreme Court Case where the children of John Miller battled for inheritance after John died instate.[10] The earliest records for John Miller were in Orange County, Virginia, where he transacted on 400 acres of land near Broadway, now Rockingham County, Virginia. These records identify John Millard witnessing land transactions and purchasing the 400 acres from James Gill in 1745. The John Millard listed in these transactions is identical to R-Miller’s oldest known ancestor, John Miller “The Quaker” and references the same 400 acres in all of the following deed records.[11]

June 1745 between James Gill of the part called Augusta County, now joyning to Orange County, and Thomas Moore.. for the sum of ___ pounds.. sells 200 acres being part of the 400 acres that James Gill purchased of Thomas Rutherford in Augusta on North River of Shenando a little above the Great Plain... (signed) James Gill (Seal), Eleanor Gill (Seal). Witnesses: Peter Scholl, Valentine Sevier, John (X) Millard. Payment of £60 for 200 acres. Recorded Orange County 27 June 1745.[12]

Figure 5

Indenture 20 June 1745 between James Gill of Augusta County and John Millard of same.. for £20.. sells 200 acres, part of 400 acres James Gill purchased of Thomas Rutherford, situated on North River of Shanando River.. part of Orange County called Augusta.... (signed) James Gill (Seal). Witnesses: Peter Scholl, Valentine Sevier, Thomas Moore. Recorded Orange County Court 27 June 1745.[13]

Two years later, in 1747, John Miller was then listed as John Millar in the sale of the same 400 acres that he (John Millard) purchased from James Gill in the 1745 deed.[14] However, the transaction record uses Millard for John’s surname (figure 6a), but he and his wife, Hannah, sign the document as Millar (figure 6b).[15] It is rare to find such a clear cut example of a surname spelling transition.

Page 13. - 4th September, 1747. John Millar and wife Hannah to Francis Hughes, late of Lancaster County, Penna., part of 400 acres patented to Thomas Rutherford, of Frederick County, and sold by him to James Gill, late of Augusta; other part in possession of Thomas Moore Teste: Mathew Skeen, Thos. Milsap. Delivered to Abra. (?) Bird, January, 1754[16]

Figure 6a & 6b

Next in 1754, the same land changes hands and John is now listed as John Miller.

Book 2-13.--Delivered to Abra. Bird Jan 1754. 400 acres originally patented to Thomas Rutherford and by him sold to James Gill , late of Augusta County. The other part in possession of Thomas Moore. Francis Hughes, late of Lancaster County, PA. Grantor, John Miller [17]

The use of “Millard” in the earliest deeds suggests Millard was the original surname, ultimately evolving into Miller, possibly due to the large German community surrounding John’s homestead in the Shenandoah Valley, Virginia. Furthermore, numerous examples of the interchangeability of the surnames Miller, Millard, and Milward exist, thereby providing no reason to suspect that an English Miller in Colonial Virginia was anything but originally a Milward. [18]

In his book, The Romance of Names, Ernest Weekley states that Millard is indeed the same name as Miller, but with the excrescent “d.” [19] Wesley further explains that the surname transition from Milward to Millard adheres to longstanding etymological processes whereby the “w” is dropped as the initial letter of a surname suffix, as in Hardwin vs. Harding and Aspinwall vs. Aspinall..[20] Thus, an “ancestry” of the English “Miller” surname is as follows: Miller to Millard to Milward. Once the standard etymological processes created the context for historical records pertaining to John Miller, the Miller and Millard’s surnames are now identical for the PF2431 Millers. Furthermore, the genetic evidence for a close relationship between the Miller and Milward samples suggests that John Miller’s heredity surname was in fact Milward prior to Millard. Returning to the Block Tree for E-FGC19003 with the above conclusions, we find the Bonsall samples now “sandwiched” between two Milward lines within the node.

The confirmation of Richard Bonsall’s haplogroup, the antiquity of the coalescence between the Milwards versus Bonsalls and Millers, the historical records of a transition for the Miller surname from Millard, the standard etymology process which show Millard and Milward as identical surnames, and the phylogenetic position of the Milward surname both upstream and downstream from Bonsall, leave but one conclusion: Richard Bonsall “the Immigrant’s” descended from a Milward family prior to his baptism in 1642. Thus, FGC19003 is now the Milward node.

Section 3: Dating Milward to Bonsall

The E-PF2431 phylogeny by Kemouche constrains the potential birth years for a viable Bonsall/Miller common ancestor to 1665±158 CE or from 1507 to 1823. The evidence in Section 1 proves that no common ancestor between Miller and Bonsall occurs more recently than the birth of Richard Bonsall “The Immigrant.” Therefore, we can refine Kemouche’s estimates for a Miller/Bonsall coalescence from 1507 to 1641, one year prior to Richard’s baptism.

YFull estimates the divergence of genetic samples at FGC19003 occurred roughly 425 ybp or about 1597 CE.[21] Taking both Kemouche’s and Yfull’s estimates into account, circa 1600 seems the most likely date for the Bonsall/Miller/ divergence.

Section 3: Overcoming the Missing Bonsall Baptism

The name of Richard Bonsall “The Immigrant’s” father, Joseph, is confirmed by Richard’s baptismal record.[22] At this time, no baptismal record has been identified for Joseph Bonsall. However, as this paper will discuss, a good estimation for Joseph’s birth year is between 1606 and 1609.

To prove the ancestry of Joseph Bonsall as the son of a Milward father, four pieces of evidence should overcome the deficiency in the baptismal record for Joseph Bonsall:

1. Identify a Joseph’s mother, Johanna Stone Milward, who marries a Milward within proper time frames and geographic location.

2. Prove that Joseph Bonsall could not be the son of the purported father, Richard Bonsall, who was Joanna Stone Milward’s second husband.

3. Identify a reason for Joseph assuming his stepfather’s surname.

4. Identify other children of Joanna and William Milward who assumed the Bonsall surname.

Section 4: Johanna Stone Milward

According to most oral traditions and written genealogies of the Bonsall family, Joseph’s mother was Joanna Stone Milward.[23] Suspiciously and serendipitously, all the genetic evidence has established a very likely surname change from Milward to Bonsall within the approximate birth year of Joseph Bonsall. Additionally, one might assume the Milward/Bonsall surname change occurred with Joseph’s birth due to the inclusion of Milward in his mother’s name.

Sifting through the historical record, only one Johanna in the Derbyshire and Staffordshire parish records fulfills all genetic and historical requirements to be the mother of Joseph Bonsall: Johannam Stones, who married William Mylwarde in 1590, Alstonefield, Staffordshire.[24]

William Milward and Johanna Stone Marriage Record

Figure 8

Future research may benefit from the conclusion of this marriage record being of Joseph Bonsall’s parents since likely Milward, and Stone relatives are listed in the same record book.

Johanna has been a source of confusion for most Bonsall family historians. Genealogical accounts of Johanna consistently list her with the three names, Johanna Stone Milward, suggesting she was married before Richard Bonsall. Though many of the same family researchers assumed that Joanna’s maiden name was Milward and listed Lawrence Milward as her father and Stone as her mother’s maiden name, no evidence corroborates these assumptions. Furthermore, the genetics alone makes Stone a more appealing option than Milward for Joanna’s maiden name. Thus, Milward must have been a previously married name and Stone was Johanna’s maiden name.

Section 5: Bonsall Generational Timeline

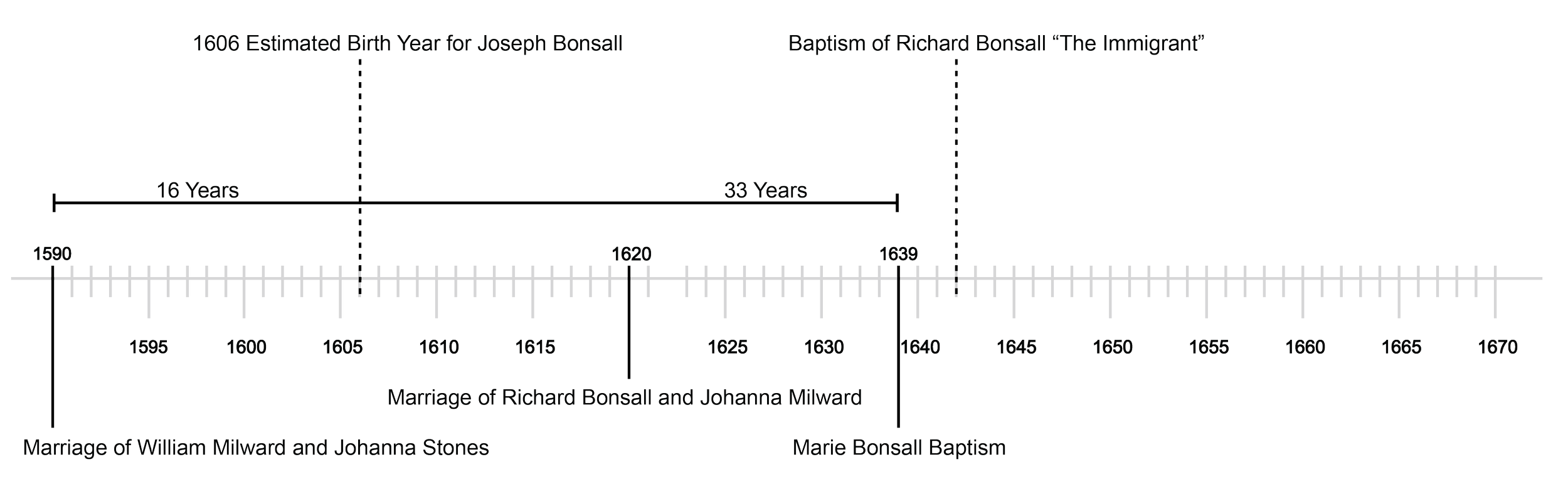

A timeline of birth and marriage events within the three generations of Richard Bonsall “The Immigrant,” Joseph Bonsall, and Johanna Stone provide the necessary evidence to refute the claim that Richard Bonsall, Sr. is the father of Joseph Bonsall. (see Appendix 4, 5, 6)

Ursula M. Cowgill’s thesis, Marriage and Its Progeny in the City of York, 1538-1751, furnishes a framework by which one can establish ages at marriage and specific birth events within the average family of England during the 17th century. The chart below lists average ages calculated by Cowgill’s authoritative work.

Cowgill’s Average Ages for Marriage and Birth of First Child

Figure 9

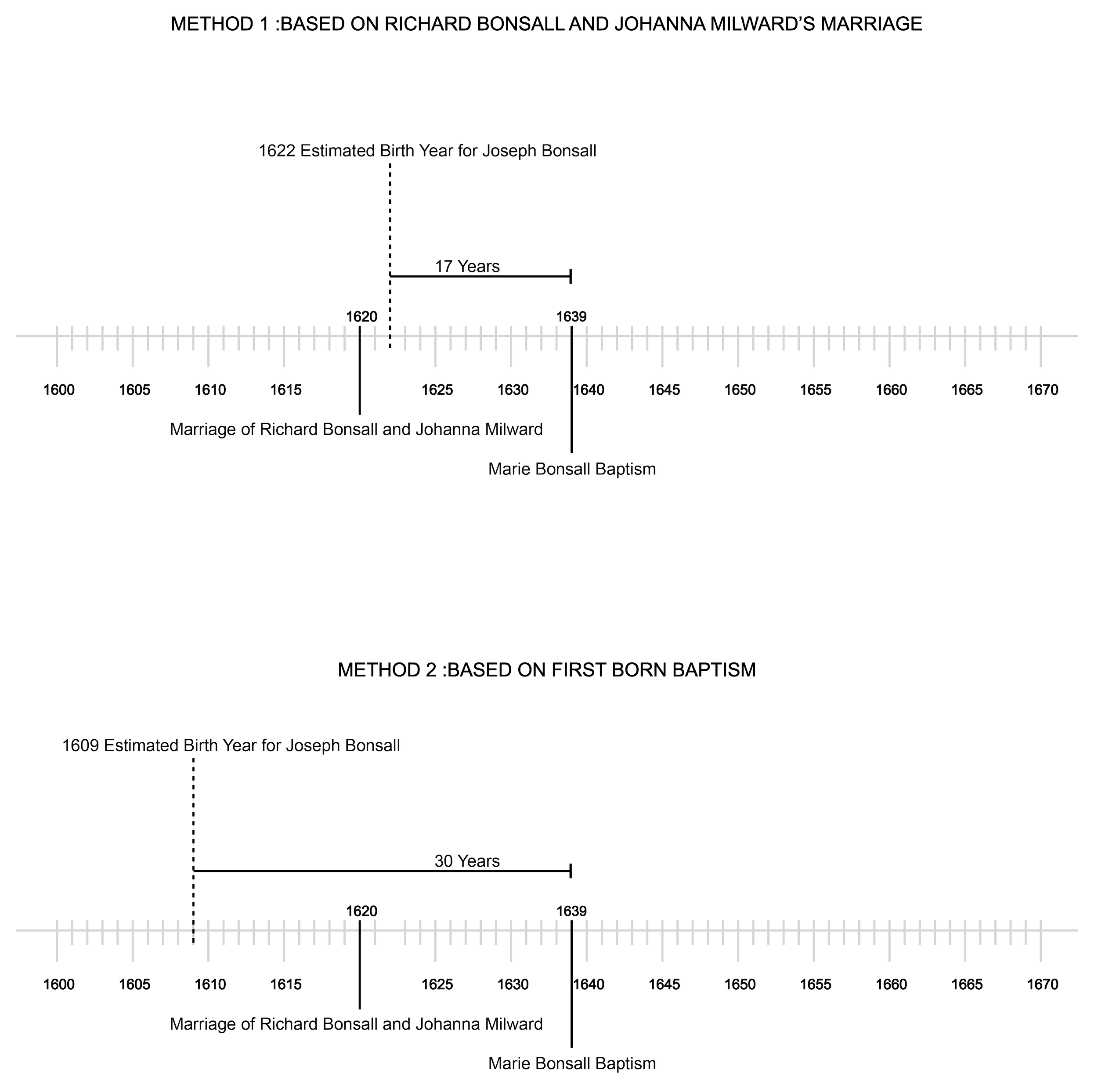

Using Cowgill’s data, one can devise two methods or starting points to approximate a birth year for Joseph Bonsall. However, these two methods result in two very different birth dates. “Method 1,” described in Appendix 4, starts with the marriage between Johanna and Richard Bonsall, resulting in a wholly ruled-out birth year. “Method 2” described in Appendix 5, starts with the baptism of Joseph Bonsall’s firstborn child and results in a birth year that fits perfectly within the evidence of a Milward paternity of Joseph Bonsall.

According to Cowgill, on average, the first child of a newly married couple during the 17th century was born two years after marriage. “Method 1” bases a calculated birth year for Joseph by assuming Jospeh was the firstborn of Johanna and Richard Bonsall and adding the two years to the date of their marriage in 1620.[25] Thus, “Method 1” produces a 1622 estimated birth year for Joseph Bonsall, assuming Joseph Bonsall was the firstborn. On 5 Mar, 1639, Joseph Bonsall baptized his firstborn child, Mariae in Hartington, Derbyshire. If “Method 1” is the correct then Joseph was sixteen years old at the birth of his firstborn (subtracting one year for the time between birth and baptism).[26] According to Cowgill, a male’s age at the time of his firstborn child was 30. Therefore, “Method 1,” which assumes Johanna and Richard Bonsall were the parents of Joseph, is unrealistic if not impossible. Not only does this method produce a birth year far outside Cowgill’s average age, but a 16-year-old male is barely within the biological capabilities to produce offspring.

However, “Method 2” does provide a workable birth year for Joseph and starts with the known baptismal year for Joseph’s firstborn child, Marie Bonsall. Again, utilizing 30 years as the approximate age of Joseph Bonsall at the time of Mariae Bonsall’s baptism in 1639, Joseph Bonsall’s birth year is estimated to 1609. Given all evidence provided in this research, 1609 is an excellent estimate. Furthermore, 1609 is eleven years prior to Joanna’s marriage to Richard Bonsall, thus adding evidence against many Bonsall genealogies claiming Richard Bonsall was father to Joseph. Thus, “Method 2” is a reasonable method to secure a birth year for Joseph likely based on Cowgill’s averages. Therefore, it is impossible for Joseph to be the son of Richard Bonsall, Sr.

Alstonefield, Staffordshire. photo credit: Andrew Mowbray (Tumblr)

Section 6: Identifying the Milward

As mentioned, Johanna Stone married William Milward in 1590. Joseph is likely the lastborn child to Johanna and William Milward since only the minor children would have assumed the Bonsall surname and birth years for Joseph’s siblings prevent him from being the oldest of the minor children.

The following is a list of likely children born to Johanna Stone and William Milward. Joane and Thomas, born in 1602 and 1605, respectively, are the only children whose parish baptismal records list both the mother and father. The baptismal records for the other children only list William Milward as the father and, therefore, might pertain to a different William Milward. [27]

1592 Joan Milward

1594 William Milward

1595 Richard Milward

1596 Thomas Milward

1597 Elizabeth Milward

1600 John Milward

1602 Joane Milward (minor in 1620)

1605 Thomas Milward (minor in 1620)

According to Cowgill, the average age of a woman at the birth of her lastborn child was 38 years old, but roughly 40% of women during the 17th century still had children after the age of 40.[28] Assuming Joseph was the lastborn child in 1609 and Johanna was 41 when she gave birth to Joseph, then Johanna’s birth year is approximately 1568. Based on her estimated birth year, Joanna was 22 years old when she married William Milward, an age that fits well within the averages calculated by Cowgill.[29]

Based on Thomas Milward’s birthdate of 1605 in the above list, it is very likely Joseph was born as early as 1606, adding only three years of a margin of error for Johanna’s age at the time of her first marriage.

Furthermore, Richard Bonsall Sr, Johanna Stone Milward’s second husband was likely born in 1565, although this date is unsourced and gleamed from what seem to be the most reliable online sources. The marriage between Johanna and Richard occurred in 1620 and the marriage record list Johanna as Johann Milward without the Stone, suggesting Milward was a married name from her first marriage[30] in 1620, Richard was 55 years and Johanna was 52 based on her estimated birth year.[31] The closeness in age between Johanna and Richard Bonsall at the time of their marriage adds further evidence for Johanna and Richard’s marriage occurring later in life and after Johanna’s marriage to William Milward. No evidence children between Johanna and Richard Bonsall exist. Therefore, it is likely Johanna was past her childbearing years when she married Richard Bonsall.

Section 7: Assuming the Bonsall Surname

Joane Milward, daughter of Joanna and William Milward, was baptized in 1602 and may have also taken the Bonsall surname. No marriage record was located for a Joane Milward, born about 1602, in the Derbyshire or Staffordshire parish.[32] However, in 1624, a Joannnam Bonsall married Johan Mottram in Hartington, Derbyshire, the same village where Richard Bonsall “The Immigrant” was baptized. In 1624, Joane Milward was 22 years old and was the right age for marriage according to Cowgill’s estimates.

After an exhaustive search no birth record was found in Derbyshire or Staffordshire for Joannam Bonsall. However, since we know Joseph had a sister named Joane Milward and Joane was minor child when her mother remarried Richard Bonsall, it is very likely Joane assumed the Bonsall surname as her brother Joseph. Therfore, it very possible Joane Milward was also the Joannam Bonsall that married John Mottram.

Joane Milward was 18 at the time of her mother’s remarriage, which makes her the eldest of the minor child of Joanna Stone Milward in 1620. With the evidence that Joane Milward assumed the Bonsall surname along with her brother Joseph, it is likely, that Thomas Milward, born in 1605, also assumed the Bonsall surname. However, no search for Thomas Bonsall was conducted at the time of this research.

Section 8: Non-Paternal Event

It was a common practice for children to assume their stepfather’s surname upon the remarriage of their widowed mother.[33] If a child had a right to an inheritance, frequently, an “alias” would be added to the birth surname, and the stepfather’s surname would be listed prior to the “alias.”[34] Thus, Joseph Bonsall would have been stylized as Joseph Bonsall alias Milward at some point if he was to receive an inheritance.

No search has been attempted to locate any of Joanna Stone Milward’s children recorded as “alias Milward.” However, no inheritance was likely administered to Joseph as the last of the many children of William Milward.

Since Johanna and Richard Bonsall married in 1620, William Milward must have died, or a separation between William Milward and Johanna must have occurred prior to 1620. There are multiple options for a pre-1620 death record associated with William Milward in Staffordshire and Derbyshire. No research has been conducted to identify which, if any, of these death records pertain to the William Milward contemplated here. Nor has any search of separation records for this marriage been completed. However, no death record is needed to secure Joseph as the son of William Milward since the historical record sufficiently fulfills the criteria outlined in this paper to overcome the lack of Joseph Bonsall’s baptismal record.

Conclusion

The DNA evidence taken from the two Bonsall samples has proven that Richard Bonsall “The Immigrant” was the legitimate paternal ancestor of the E-PF2431 Bonsalls and that the Milward surname occurs both upstream and downstream from the Bonsall samples in the phylogeny. Given the dates of Richard “The Immigrant” and his sister, Marie’s, baptism in 1642 and 1639, respectively, their father, Joseph Bonsall, must have been born about 1609 or perhaps as early as 1606, which is eleven years prior to Richard Bonsall Sr. and Joanna Milward’s marriage in 1620. Thus, Richard Bonsall Sr. cannot be the father of Joseph Bonsall or the grandfather of Richard Bonsall “The Immigrant.”

Based on the tradition that Joseph Bonsall’s mother was Johanna Stone Milward and the DNA evidence proving a surname change from Milward to Bonsall at the time of Joseph’s birth, one record provided a suitable candidate for Johanna within the proper timeframes, matching Cowgill’s averages and fulfilling the necessary requirements of the DNA test results. That record identifies William Milward of Alstonefield as the father of Joseph Bonsall and the grandfather of Richard Bonsall “The Immigrant.”

Further Avenues of Research

William Milward the Aleshouse Keeper

This paper will not address the life of William Milward. However, one record identified in Alstonefiled might prove beneficial for future research. In 1599, “Wm. Milward” is listed as an ale keeper from Alstonfyld in the Staffordshire Quarter Sessions Rolls.[35] This record may pertain to William Milward, the husband of Joanna Stone Milward. On March 19th, 1605, William and Joane Milward baptize a son Thomas, and the baptismal record indicates the family is from Alstonefield.[36] Other Milwards in the Alstonefield parish records are assigned various other locations or no specific area at all. Both William Milwards, the Alehouse proprietor and the father of Thomas, are in Alstonefield at the same time and look to be the same age. Therefore, the two records may refer to the same William Milward.

Milwards of Eaton Dovedale

A close genetic cousin to the E-PF2431 Milward family is the Pegg family, which is described in great detail in Thomas W. Charlton’s authoritative genealogical work in Journal of the Derbyshire Archaeological and Natural History Society.[37] Suppose these two paternal lines held similar social positions and remained geographically close. In that case, the Milward pedigree could likely be extended through research into the Milwards of Eaton Dovedale. A significant amount of documentation can be found in various sources regarding the Milwards of Eaton Dovedale.

Most genealogies list William Milner alias Milward alias Millener late of Eaton by Doveridge and Alice, Ann or Agnes Kniveton as head of the Milward family tree.[38] However, other resources also list Simon Milward or Mulward, killed by Hugh de Stredeley in 1365, Penkull, Staffordshire, as the ancestor of William Milward of Eaton Dovedale.[39]

Mouldridge Grange Ownership and John Milward of Brandley Ash

At the time of the Bonsall residence in Mouldriddge Grange, the ownership of the grange was held with John Milward of Snitterton, a Milward of Eaton Dovedale. John Milward died in 1670, leaving one son, Henry, and two daughters, Mary and Felicia. Henry died in 1672, and the estate of the Milward family was passed to John Milward’s daughters.

John Milward of Snitterton’s father, John Milward of Bradley Ash, purchased Mouldridge Grange in 1582.[40] From there, Mouldridge Grange passed to the Milward.

John Milward, of Bradley Ash, died in 1633. In his will, a John Bonsall was mentioned and received money from the Milward estate. (see Appendix 6) In John’s will, John Bonsall is listed with a group of individuals: William Blount, John Bonsall, Robert Wright, and Matthew Wright, “my shepherd.”

William Blount must be related to John Milward of Bradley Ash, as Sir Thomas Pope Blount, bother-in-law to John Milward, is also listed in the will and is a likely relative of William Blount.

An interesting coincidence occurs with the inclusion of two individuals from a Wright family in John Milward’s will. A Wright paternal line has tested positive for the E-PF2431 haplogroup and is closely related to the Pegg line.[41]

Because John Bonsall is listed in the will alongside a member of the Blount family suggests a very close relationship between the Milwards and at least one branch of the Bonsall family. No historical records for John Bonsall have been found, and his connection to the Milward family is tenuous. However, given the information contained within this report, John Bonsall is an excellent avenue for further research.

Milwards of Eaton Dovedale and Stone Family

Though the original record has not been reviewed, a lawsuit was found in 1619 between Thomas Stone and Richard Milward with others realting to land in Stramshall, Staffordshire. Since the record seems to be around the time of the death of William Milward, who married Johanna Stone, perhaps this record may relate to his death in some way.

[1] Henstock, pg 9

[2] History of Chester county, Pennsylvania, with genealogical and biographical sketches

[3] see Appendix 1

[4] The low concentration of PF2431 in North Europe and especially Great Britain provides a unique opportunity to identify closely related individuals with limited DNA data. The heatmap of PF2431 in Appendix 2a shows, along with various academic research, that PF2431 is one of a few genetic markers for the Amazigh people of North Africa.

[5] Ancestry reports for both GB and RB in Appendix 3

[6] See footnote 4

[7] https://blog.familytreedna.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/big-y-700-white-paper_compressed.pdf

[8] See Appendix 1

[9] See Appendix 2b

[10] The date of John Miller’s death, the issues surrounding his estate, and connected this John Miller to the John Miller of Linville Creek are gleaned from multiple sources, including Virginia Supreme Court, District of Kentucky, Order Books 1783-1 p. 153, the appraisal of his estate on the 16th, Sept. 1783 in Lincoln County, Kentuck and the probate account of his wife Hanna in 1806, Mercer County, Kentucky. From these records, we can tie this John Miller back to the John Miller of Linville Creek through a land transaction with Taverner Beale in Dunsmore County, Virginia.

[11] See John Miller “The Qaker’s” data at https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Miller-78424. Full paternal line of R-Miller is listed in Appendix 4.

[12] Orange County, Virginia Deed Book 10 pg 601

[13] Orange County, Virginia Deed Book 10 1745-1747 pg. 601

[14] August County, Virginia Deed Book 2, pg 13

[15] August County, Virginia Deed Book 2, pg 13

[16] Chronicles of the Scotch-Irish Settlement in Virginia, 1745-1800. Extracted from the Original Court Records of Augusta County” by Lyman Chalkley. pg. 269

[17] August County, Virginia Deed Book 2, pg 13

[18] An appropriate example of the interchangeability of various Miller forms is in The Patent Rolls, 20 Edward IV - Part 1- May 14th, 1480: “General Pardon to William Milner alias Milward alias Millener lat of Eyton by Dovebrigge, co. Derby, ‘yoman,’ alias of Dovedale, co. Derby ‘husbondman,’ of all offences committed by him before 12 May. by p.s.”

[19] Weekley, pg 25

[20] Weekley, pg 39

[21] https://www.yfull.com/tree/E-FGC18958/

[22] DRO M71 vol. 7

[23] This statement is based on various Anstry.com trees, written histories online and other online sources in which a cursory review was made.

[24] https://www.findmypast.com/

[25] Cowgill, Table 1

[26] Accessed to this record was obtained from FindMyPast.com:

[27] Alstonfield, Joan - pg 99, William - pg 100, Thomas - pg 100, Elizabeth - pg 101, Joane - pg 67, Thomas - pg 69. The other children baptismal records were accessed from FindMyPast.com.

[28] Cowgill, pg 57

[29] Cowgill, Table 1

[30] Alstonfield, pg. 152

[31] This calculation uses the averages from Cowgill’s work and the marriage date in the parish records.

[32] Cowgill, Table 1

[33] https://isogg.org/wiki/Non-paternity_event

[34] https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Use_of_Aliases_-_an_Overview

[35] Burne, pg 137

[36] Alstonfield, pg 69

[37] Charlton pg 126

[38] Many published books on the history of England include the pedigree of the Milwards of Eaton Dovedale. However, the History and Antiquities of the Town and Neighbourhood of Uttoxeter, with Notices of Adjoining Places (1886) brings together those various Milward family histories and shows the all connect together. pg 328

[39] See Redfern pg. 254. The author states that Milwards of the same family married into the Pembridges= and the Knivetons. William Milward of Eaton Dovedale married the Kniveton and a Richard Milward Joane or Jane Pembridge. Richard’s grandfather was Simon Milward as listed in The Visitations of the County of Sussex Made and Taken in the Years 1530, Vol. 53 pg 13. The visitation lists Simons death as “48 Edw III.” However, the following refernce shows that his death date was actually 38 Edw III. Staff. The Jury of Pyrhull, presented that Hugh de Stredeley, the brother of John de Stredeley, living at Penkhull, had feloniously killed Simon le Meleward at Penkhull on the Thursday the Feast of St. James 38 E. III - Please of the Crown

[40] Tiley, pg. 303

[41] See Figure 8

Bibliography

Alstonfield, Eng. (Parish) and Staffordshire Parish Registers Society. Alstonfield Parish Register [1538-1812] Part I-[V] July 1902-[Dec. 1906]. 5 pt. London: Priv. Print. for the Staffordshire Parish Register Society, 1902. //catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100380402.

Charlton, Thomas W. “Some Account of the Family of Pegge, of Shirley, Osmaston, Ashburne and Beauchief, in the County of Derby.” Journal of the Derbyshire Archaeological and Natural History Society 1 (1879): 125–27.

Cowgill, Ursula M. “Marriage and Its Progeny in the City of York, 1538-1751.” University of Pittsburgh. Accessed May 5, 2022. https://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/anthpubs/ucb/text/kas042-004.pdf.

Redfern, Francis. History of the Town of Uttoxeter. xi, 368 p. London: J.R. Smith, 1865. //catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/011545418.

Great Britain., S. A. H Burne, Staffordshire (England)., and Staffordshire Record Society. The Staffordshire Quarter Sessions Rolls. Vol. 1 (1581). Half-Title: Collections for a History of Staffordshire, Edited by the William Salt Archaeological Society, in Conjunction with the Staffordshire County Council ..., v. [Kendal: T. Wilson & Son], 1931. //catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/010462397.

Henstock, Adrian. “The Early Derbyshire Quakers and Their Emigration to America.” Derbyshire Miscellany 8, no. Spring 1977 Part 1 (1977): 7–9.

Tilley, Joseph. The Old Halls, Manors and Families of Derbyshire. Simpkin, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent and Company, 1893. https://archive.org/details/oldhallsmanorsa02tillgoog/page/n318/mode/2up?q=moldridge.

Weekley, Ernest. The Romance of Names. London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, W., 1922. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Romance_of_Names/LtzfAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1.

Appendix 1

Appendix 3

Richard Bonsall “The Immigrant” bap. 1642

Benjamin Bonsall b. 1687

John Bonsall b. 1716

Benjamin Bonsall b. 1756

Edward Bonsall b. abt 1790

George W. Bonsall b. 1824

Walter Bonsall b. 1852

John Richard Bonsall b. 1887

William Ross Bonsall b. 1924

Private Bonsall

G-Bonsall

Appendix 4

John Miller “The Quaker” b. about 1708

John Miller Jr. b. abt 1730

Abraham Miller b. abt. 1751

Aaron Miller b. 1782

Tyre Miller b. 1806

John D. Miller b. 1837

John Otha Miller b. 1879

Orlando William Miller b. 1908

Private Miller b. 1942

R-Miller

Appendix 5 & 6

Figure 7

Appendix 8

Below is a transcription of the will of John Milward of Bradley Ash which is located at the KEW in the Records of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury. The transcription was completed by the author of this research and is not trained to perform such transcriptions. For verification, any information gleamed from this transcription should be verified with the original copy of the will, which can be found online. (John Milward's Will)

1633 John Milward of Bradly Ash in the Countie of Derbyshire, being in perfect mempry and health, (thanks be to God), do by this my own hnd writing ordain and make this my last will and testamament in manner and form following ____ _____ my sould to Almighty God with assured hobe to be saved and _____ not by any ____ or ____ of mine owne – but by the great and infinite merit of God, and the only _______ of hisSon Jesus Chirst my _____ Savior and only _____ _______, I appoint my body to the care ______ ot ______to be buried at the discretion of my Exicutor without any _______. ____ or ______, but only wityh charitable respect to th poor. And to the poor of Thorpe, I give ______ shillings. Tp the poor of Mappleton ____shillings, toe the poor of Bently ____ shillings. To the poor of Ashbourne and Compton five pounds, to the poor in Whetton, forty shillings, to the poor of Doveridge forty shillings, to the Poor of Marchington fortie shillings, It ____where mt loving good _____ Mr. Robert Milward deceseased did by his half will gove to the poor in Ashbounre twenty shillings, to the poor of Whetton, twenty shillings, to the poor of Doveridgem twenty shillings and to the poor of Thopre, five shillings, ………. I do will and appoint the said som of fifit five shillings to be yearly paid _____out of my rents and profits in my manor of Thopre in the said county of Derby during all the said term of ______, ….Item, I so to my ___wife all my ____of term of _____whatsoever. To hold the same to her and her assigned for all the ______..... Item. I do give to my brother -in-law. Sr. Thomas Pope Blount, Knight 5 pounds. Item I do give to my loving son-in-law, Sir Henry Agard knight, my best ______ or mare. And I do give to my loving daughter his wife, twenty pounds. Item, I do give to my loving kindsman Mr. Thomas Milward esquire, five pounds. Item. I do give to _____out of my household servant whentie shillings____. Item. I do give to William Blount, John Bonsall, Robert Wright, and Mathew Wright, my sheppard and servant vizt? To care of them ___shillings. Item, I give to Margaret Weirfell? Twenty Shillings. Item, I give to Henry Moltorablim my servant fourtie shillings, All my debt paid my funeral expenses and _____discharged. All the rest? Of my goods, Chattle, _______, money, and debt whatsoever, I give to my lovin wife whim I make my sole Executrie assuredly_______that and during the time of our living together, she has married her self with commendable ______ both for her own reputation, my profit and her _________ _________of our children’s education and well doing. So that now after my death perform this my last will according to my true intent and _______. And I do _______ _____ my said son-in-law Sir Harry Argard and my said loving kinsman Mr. Thomas Milward equire to be over said of this my last will and testaamnt preying them to be aiding and _______to mt said wife a

John Milwarde Robert Poote (Boote or Boothe)

Marit Millward relicte

Figure 9

Phylogeny provided by Yacine Kemouche 16 Mar 2022